“Eat something,” he commanded. His lips were a firm line.

“No thank you, I’m not hungry,” I said, with a meek smile, hoping to seem as if I knew what was best for me. I was in a hospital bed in Cambodia, a 20-year-old white girl scared and alone in a place with no room for self-pity.

“Eat something,” he repeated, louder – his narrow eyes widening behind his glasses. I was glad the old Cambodian man in the bed opposite was sleeping. He slept most of the day due to nights spent with violent coughing fits sounding as if his lungs were trying to squeeze through his windpipe. Following five or six coughs, he would spit in a tin bucket. An American patient said he believed the man suffered from tuberculosis. When I arrived, he was relieved to see another English speaker, but I had very little energy for speaking. I don’t think he liked me much, and I didn’t blame him – I didn’t like myself with dengue either. I could only afford short sentences and nods, and his attempts at communicating died quickly.

“Where are you from?”

“Norway.”

“Travelled for long?”

“Yeah.”

“I’ve got salmonella, what are you in for?”

“Dengue fever.”

He left sometime while I was sleeping.

“Okay,” I said to the doctor, defeated. “Noodles.”

I hadn’t been eating much for a while. It was as if my stomach had fallen asleep and didn’t speak to my brain anymore. It never told me it was empty – that I needed food. I’d later learn that it was caused by an E.coli blood infection. I suppose bad news travel in pairs. Bones began showing, starting at my hip, then my shoulders, lastly my ribs.

By extreme misfortune, it was my second hospitalization caused by dengue fever in my six months of traveling, and with the little English the doctors knew, they assured me it could be fatal. They said the second round was bad news. Blood could start to wander in places it shouldn’t. Once I told my parents of my situation, my dad packed his bags – disregarding any protests as he had whenever I had been overtired as a child. I was mortified that he had to save me from my own adventure, yet relieved for feeling less alone.

“Is not food,” he said, but still jotted something on his clipboard. I shifted in my bed, and felt the needle move beneath my skin. I didn’t know it was procedure to insert drips at the crook of the arm, nor pinning it down using bulky layers of sports tape. At least I’d never seen it done on Grey’s Anatomy – which was as far as my experience with hospitals went. Like so many things, this was done a little different here. At the slightest movement, the needle would dance, toying with the elasticity of my vein. I grimaced, but knew there was no sympathy found in this building.

The room was white and bare, and the windows were frosted and barred – only allowing for the illusion of daylight. Aside from the man with the cough and me, the rest of the beds were empty. I doubted that there was a lack of sick people – only a lack of wealthy, sick people. With a long fingernail, the doctor tapped the suspended bag of antibiotics above me. The tube connecting it to my arm stirred briefly. I knew from my first round of dengue that antibiotics had no part in the treatment, but my respect for white lab coats and bespectacled stares was crippling.

At the previous Cambodian clinic, I had attempted to learn what medicine they gave me.

“What is this?” I gestured towards the needle they prepared.

“Yes. No. Yes. No. Medicine. Injection,” they said, and nodded once before they inserted the needle into my arm, the medicine burning and bulging as it went through. I cried from the pain and for feeling so helpless. They giggled at my tears, instructing me to massage along the blood flow to relieve pain. Any preconceived notions of being independent and world-savvy were scattered and hiding – remaining was a frail, bony thing in a bed across the world at Christmas, wanting nothing but to snap her fingers and sit beside the tree at home. This time around, grateful they didn’t inject me with fire, I objected to little.

The doctor left without a word, his feet clacking against the marble floor. He was the only one with noisy shoes, announcing his arrivals and exits like a fanfare. The nurses and cleaners moved about on silent feet, the only sound being the swoosh of the glass doors separating the sick from the rest of the world. The doors opened as his clacking feet approached and hot air rushed in to meet the cold. Fever ridden and freezing, the warmth felt like a hug in a snowstorm.

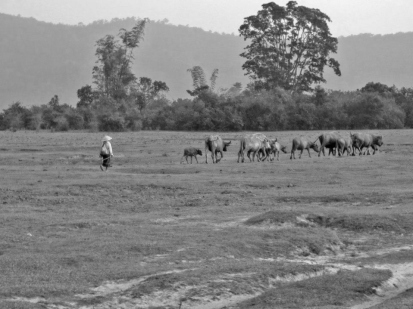

Before dengue, I worked at a hostel on an island called Koh Rong. Reachable by old, wooden boats burbling into the ocean, it was situated a couple of hours off the coast of Sihanoukville. Paradise on land they called it, and there was no name more fitting. Here the jungle kissed the ocean, separated only by a strip of powdery sands and a handful of shacks strewn about. Sans roads, sans stress, sans ATM’s, one merely kicked off ones shoes upon arrival and left barefooted. My boss was a man named Bunna – an orphan from a river delta in northern Cambodia – Illiterate in every language, but fluent in four. He had a young daughter in England, and sometimes we would practice writing in my notebook, so he could write her.

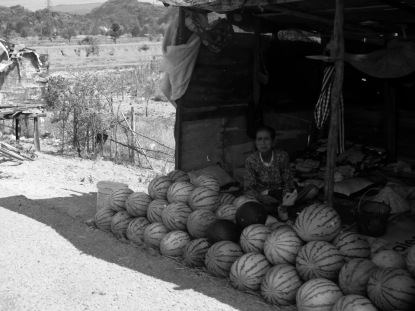

It was the beginning of rain season and business was slow, so I spent the days snorkeling, exploring the jungle and picking seashells, shards of glass and garbage on the beach. Cambodia is a dizzying concoction of beauty and horror, pristine and polluted – conches and syringes side-by-side. Having coaxed Bunna into adding some color to the place, I had taken it upon myself to paint the naked boards of the hostel bright blue. Balancing on a red, plastic chair shivering under my weight, I painted with sweat dripping from my forehead until the heat became unbearable and I jumped in the sea.

I thought it had been the island bug when I first fell ill – just a passing cold. I had a few mosquito bites, but thought little of them. People said dengue wasn’t present in paradise, but everyone’d caught it lately. They retreated into dark rooms with fans whirring loudly to relieve the heat whenever electricity was available, which it very rarely was. It started out softly – a fever so mild it felt like a hangover. In the day, my dorm room was a sweltering box, and in the silent absence of the fan, the pitter-patter of rat-feet running along the floors and hanging-beams grew into thundering noises. Instead, I occupied shaded hammocks and wicker chairs, leaning into travelling breezes whilst waiting for the bug to pass. Except it didn’t. Defeated, I left the island. Just for one night, I told myself, looking back at the people waving on the dock. Just for one night, I swore, as the island became a speck on the horizon.

“Noodles.” I hadn’t realized I’d fallen asleep – my eyes readjusted to a nurse hovering over me. The smell of spices made my stomach turn. Between hourly blood pressure measures, endless trays of pills, and cleaners leaving lights on and doors open at night; the force-feeding proved the most difficult. My stomach had forgotten how to stomach, and they seemed to blame it entirely on me. In Cambodia being sick was a matter of blame, not sympathy.

“Thank you.” I made no reach for the cup on my bedside table – but the nurse seemed in no rush to leave. I suspected the doctor had told him of my ways. Eventually I picked it up, ate a few mouthfuls, and watched him leave before putting it back down. I noticed a rash forming on my arms and my palms, they’d warned me that might happen – blood seeping through the veins – I decided not to investigate my legs. Instead, I dialed my mother, but the connection failed. I felt like an island.

During my last meal on Koh Rong, a fishbone lodged itself horizontally in my throat. “Eat,” Bunna said, and handed over a ball of rice. The bone didn’t budge. “Drink,” he said, handing me a bottle of water. “You cry too much,” he complained. Truthfully, I hadn’t noticed I was crying. “Eat,” he repeated, handing me another rice-ball. I was reduced to a blubbering toddler. Finally, the bone broke and I laughed, relieved, cheeks wet with tears. I wondered how I’d ever believed growing up in Norway had prepared me for the world, when a fishbone felt so final.

The IV-pole doubled as a crutch as I walked down the green-lit corridor towards the bathroom. Here were linoleum floors, and bare feet would stick. Blood traveled up the intravenous tube at the change of pressure – a red snake fighting a yellow one and winning. Keeping my arm low prevented blood from escaping, so whenever no one was around I walked hunchbacked with my arm stretched limp towards the floor.

I flushed and shuffled back to my bed, where I noticed the frosted windows had blackened. About to drift off to sleep, I heard a voice I knew so well, yet it seemed as if it travelled to me from another world. I turned to see my dad standing in the open door.

“Let’s go home,” he said casually, as if I was eight and he was picking me up from school, and it felt like I had waited forever.